An introduction to Jesper Just

by Nina Folkersma

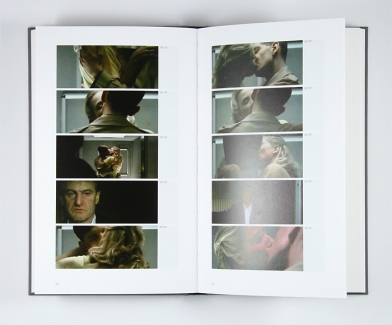

published in Jesper Just. Filmworks 2001-2007.

1.

Western philosophy has never had a great liking for emotions. Classical philosophers such as Plato, Spinoza and Kant concurred in the view that undergoing an emotion undermined rational insight. Emotions, or ‘passions’, were blind forces that overwhelmed the individual and turned him into a ‘passive’, unthinking object. These philosophers often characterized emotions as ‘instinctive’ or ‘feminine’. Like women and animals, they held, an emotional person was immune to active control or reflection by means of the rational mind.

Emotions take a central place in the work of Jesper Just: sorrow, loneliness, uncertainty, fear and, above all (as is evident from the titles of his works) yearning and love. In works such as Invitation to Love (2003), No Man Is an Island (2004), The Sweetest Embrace of All (2004) and It Will All End in Tears (2006), we see how the characters – almost exclusively men – either struggle to repress their feelings, or give unfettered rein to them. One man, physically and emotionally restrained in his close-fitting suit, unexpectedly starts dancing on the table; a young man bursts out ininto song with an a capella rendition of Roy Orbison’s Crying, tears rolling down his face; an older man falls slowly, and euphorically backwards amid a shower of rose petals. That Just’s characters have a flair for sentimentality or melodroma cannot be denied. But does this emphasis on emotion imply that those individuals are at the mercy of blind, uncontrollable forces? Are they, as the classical philosophers would hold, devoid of all rational consciousness and incapable of reflecting upon their situation?

According to the contemporary American philosopher Martha Nussbaum, the traditional opposition between emotion and reason is no longer valid. In her book Love’s Knowledge, she argues that the emotions consist not only of physical sensations but also of cognitive ones, that emotion can in fact create insight and understanding. Although this “knowledge of the emotions” is not primarily discursive, our emotional experiences make us conscious of our perspective on the world and on our often deep-rooted views on what matters to us in life. Jesper Just focuses on human emotions, not for their emotional effect on the viewer but to give the viewer an insight into the patterns of sociocultural values that underlie them.

2.

“Who will write the history of tears? In what societies, in what ages, did people cry? Since when are men forbidden to cry (but not women)? Why did ‘sensitivity’ change at a certain point into ‘sentimentality’?” This is what Roland Barthes asks in his Fragments d’un discours amoreux

Images of masculinity have always been fluid. In Greek antiquity and in the seventeenth century theatre audiences would weep openly. Today, crying among men is mainly seen as evidence of weakness. A real man is supposed to contain his emotions, to be inviolable, intellectual, pragmatic, virile and dominant. That, at least, is the image of man portrayed in classic most Hollywood films. The tTransgressingon of social and cinematographic conventionals on the representations of masculinity is a crucial element of Just’s work. His videos are often set in ‘typically masculine’ surroundings, such as a men’s club, a strip- joint or a deserted harbour quay, and the male protagonists are usually dressed in similarly conventional clothing. Just thereby creates a visually coherent stereotype to which the public automatically attaches a corresponding set of behaviours. But then unexpected things happen. In The Lonely Villa (2004) we see several distinguished-looking older men in dimly lit surroundings, each seated in silence at his own table waiting for the telephone before him to ring. Once the protagonist’s phone finally rings, the face of the young man at the other end appears, singing a love song in a soft, clear voice. The older man responds with a new song, and gradually his waiting companions all join in, like the chorus of a classic Greek play. The tenderness of the men contrasts with their appearance and the situation, so at firstinitially giving the scene has an absurd, comical aspect. In the end, however, its poignancy predominates: these men are not ashamed to show their feelings, even in public, even in the presence of other men.

Song and music play an important part in the videos. The lyrics articulate the feelings and thoughts that the men dare not speak out loud. Dance is another recurrent element. Along with song – Song and dance, both of which are highly physical modes of expression, – they are often the only mode of communication in Just’s videos. The man who climbs barefoot onto the table in Invitation to Love (2003) slowly begins to perform a seductive dance for a younger man. At first the young manlatter responds with an amused, slightly erotic gaze. Their relationship remains unclear, however. The context suggests a business relationship, but they might equally be father and son, or perhaps lovers, as the look in the boy’s eyes seems to suggest. The dance of the father- figure, clumsy and pathetic, betrays his vulnerability and his acute longing for contact and intimacy. The conventional portrayal of masculine identity, – for example, the image of the father as a cold, and distant man and the son as an uncertain youth desperate for recognition, – is thus undermined.

3.

Much has been written in recent decades about the role of representation in the construction of identity, especially in feminist theory. The connections between representation and power, or between looking and being looked at, and the associated gender differences, form a central point of discussion. A significant impetus towards exploring the gender status of the viewer was given by Laura Mulvey in her article “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. This article, published in 1975 has long dominated academic thinking about the gaze, and has regularly been cited in discussions on the work of Jesper Just.

Mulvey equates the eye of the camera to with the standpoint of the male spectator, who sees himself represented by the (male) hero of the film. The object of the camera’s gaze of the camera is the heroine, who is placed in the position of a passive object (of lust) for the visual enjoyment of the male audience. Jesper Just instead places the man at the centre of looking. In one of his videos, A Fine Romance (2004), he explicitly reverses the traditional roles. A young man performs an erotic pole danceing act while a young woman greedily tries to take possession of him with her eyes. The camera explores the artfully lit breast chest of the young man, filming him as an attractive visual object entirely in tune with the classical rules. The conclusion Laura Mulvey draws in her article is that it is necessary to abolish the pleasure of looking as supplied to us by traditional Hollywood film. The first blow that can be brought to the cinematic conventions is to “liberate” the gaze of passionate submission by transforming it into a critical, analytical act. This “disidentification strategy”, Mulvey writes, undoubtedly destroys the satisfaction and privilege of the “invisible guest”. The question is, what remains if the pleasure of looking is destroyed, what remains? “Intellectualized unpleasure”?

As much as Jesper Just may align himself with Mulvey’s critique of the dominantly sexist, heterosexual and chauvinist manner of portrayal in the mainstream media, there is one fundamental difference: Just does indeed offer us visual pleasure. The first thing to strike us about his films works is the exceptionally stylized, aesthetic visual language. The elegant camera movements, the refined chiaroscuro, the perfect casting and setting – every detail reveals that Just is working with a carefully selected team of professional actors, singers, composers, photographers, camera operators and lighting/sound designers. His productions consequently have all the gloss of a technically immaculate Hollywood motion picture. Thanks to these formal qualities, and also to the fact that he operates explicitly within the domain of fiction, Just stands in contrast to a recent generation of video artists who portray ‘hard reality’ in a documentary fashion, often using a deliberately amateurish style. Just carries the viewer along byWith his seductive images, Just carries the viewer into an imaginary world where, instead of conforming to mainstream fantasies, the protagonists live out their own dreams and yearnings.

4.

Martha Nussbaum writes that the style of a work of art may stimulate a “style of thinking”. Indeed, she considers the style or form to be the most important aspect of a work. This is certainly true in the case of Jesper Just. The gender politics and critical subtext of his work are invariably packaged in a highly attractive form. Linear narratives, plot and character development are merely secondary. The main focus is on the subtleties of human expression: the glances, the gestures and, either whether contained or explosive, the emotions. Just succeeds in rendering these with utmost precision and with impressive conviction. There is no trace of irony, let alone ridicule. When his men sing, cry or dance, they do so without embarrasment and with an evident feeling of mutual trust. The strength of Jesper Just is that he succeeds in conveying this solidarity and emotional interdependence to his audience. We know these men. We share their sorrow and their cravings. And what is sweeter than the consolation of recognising oneself?

Literature

Martha Nussbaum, Wat Liefde Weet. Emoties en moreel oordelen. Amsterdam: Uitgeverij Boom/Parrèsia, 1998, p. 21. [Translation of: Martha C. Nussbaum, Love’s Knowledge: Essays on Philosophy and Literature. New York: Oxford UP, 1992]

Roland Barthes, Uit de taal van een verliefde. Utrecht: Uitgeverij IJzer, 2002, pp. 106-108 (Lof der Tranen). [Roland Barthes, Fragments d’un discours amoreux (1977); English translation: A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments] The quoted passage is translated from the Dutch.

Laura Mulvey, “Visueel genot in de film” (Dutch translation by Karin Spaink), in Karin Spaink (ed.), Pornografie bekijk ’t maar. Een politiek-feministische visie op seksualiteit. Amsterdam: Van Gennep, 1982, pp. 119-135. [Originally published as “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Screen, Autumn 1975]