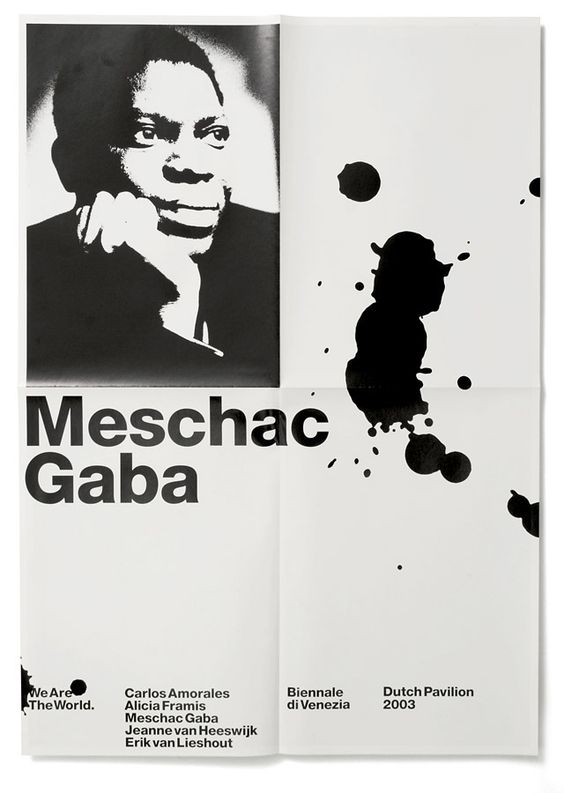

Meschac Gaba

by Nina Folkersma

published in We Are The World, Biennale di Venezia, Dutch Pavilion, 2003

Meschac Gaba enjoys travelling, he loves cities on the water, and he relishes vitality, movement and people around him. So Gaba is truly at home in Venice. He grew up in Cotonou, a city on the coast of Benin, and for a number of years has been living in Amsterdam, a city built on water and also sometimes described as ‘the Venice of the North’, and he must feel like a fish in water here. Yet, in his own words, he had never dared dream that he would ever represent a country at the Venice Biennale. Like many other African countries, Benin does not have its own pavilion on the Biennale grounds. To his own amazement, he is now standing in the Netherlands Pavilion, along with four other artists. But Gaba would not be Gaba if he were not to add an ‘African’ ingredient to the mix.

Gaba has constructed a bar in the Netherlands Pavilion in the form of a wooden boat, complete with bar staff, glassware and specially designed labels for the bottles. Free ginger tea and ginger cocktails will be poured at this Ginger Bar during the opening days and weekends of the Biennale. Ginger is renowned for its stimulant and medicinal effects. For many years Meschac Gaba thought that ginger was native to Benin. As a child he always drank ginger drinks, so he automatically assumed that it was something typically African. The fact that ginger originally comes from Asia and was introduced in Africa through trade makes it the ideal ingredient for Meschac Gaba’s work. Trade, exchange, mutual influence – and consequently confusion about origin and authenticity – are the important themes in his work.

His most famous project is the Museum of Contemporary African Art, a fragmented museum consisting of individual museum spaces, which are temporarily housed in existing art institutions. It began in 1997 with the Draft Room in the Rijksakademie voor Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam, where he was studying. In the ensuing years he added a museum shop, library, restaurant, music room and other spaces, and the twelfth and last room was recently realized during Documenta11: the Humanist Space. Gaba – in the tradition of Duchamp and Broodthaers – uses his virtual museum to question the structure and authority of the museum as we have known it since the 18th century. More specifically, he raises questions about the way in which other cultures are presented and interpreted in Western museums. By founding a Museum of Contemporary African Art, Gaba wants to show that contemporary African art cannot be reduced to a singular and so-called original set of national characteristics. And in this he takes a stand against the still regularly aired conception that the work of a non-Western artist who employs the vocabulary of Western modernism is no longer sufficiently ‘authentic’ or ‘African’. This stubborn prejudice assumes that modernism is an exclusively Western achievement, but forgets that modernism itself is also the product of exchange and commingling with other cultures.

For the sake of clarity, it should be noted that the Ginger Bar in Venice is not part of Gaba’s Museum of Contemporary African Art. It does contain aspects that characterize his earlier work. Just like Gaba’s nomadic museum, which offers an actual model that is much more lively, mobile and functional than the traditionally contemplative European museums, the Ginger Bar also adds a dynamic element to the Netherlands Pavilion. Again it is a project that is first and foremost a social gesture, a positive complement to an existing (and limited) structure. Gaba’s work offers the visitors to the Biennale a social meeting place where people can discuss, drink and network. And where at the same time, thanks to the stimulating effects of the ginger, the visitor is prompted to think about national ‘identity’ and representation.