ARTICLE – APRIL 2012

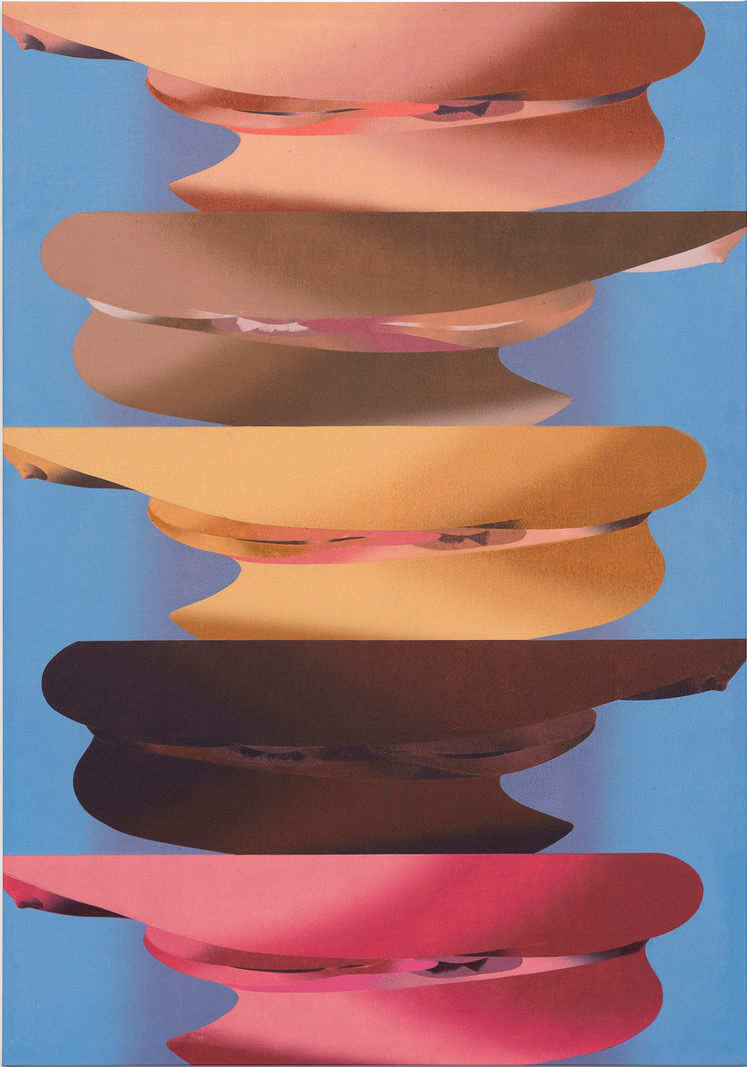

In a public park in the Hague, British artist Nils Norman (born 1966) has devised an unusual work of art: one that grows and blossoms and produces delicious fruit and vegetables. Norman’s “Edible Park” was developed using the principles of permaculture, a form of vegetable gardening in which different plants are combined in such a way that they complement one another’s needs as they grow. More than just a gardening model, permaculture is a nature-based design philosophy that can be used as a guide for architecture, product design and to improve society in general. In Eetbaar Park | Edible Park Norman explains his methods, his sources of inspiration and the artistic and social-critical context around his work. The book contains a wealth of visual material and a DIY section explaining permaculture methods that can be applied to the balcony or backyard garden.

A conversation with Nils Norman and Peter de Rooden

By Nina Folkersma

Published in: Nils Norman, Eetbaar Park/Edible Park, Valiz, Amsterdam | Stroom Den Haag, 2012

EXCERPT:

Edible Park is a multi-layered project that touches upon many different and important issues, like food production, urban development, permaculture principles, bottom-up organizational methods, utopian thinking, art in public space, community art. If you were to choose one term from this ‘word cloud’ that best represents your personal interest in the project, what would it be?

NILS NORMAN: I would choose ‘utopia’, because for me it has lots of different meanings. I don’t think Edible Park is utopian per se, but it can be framed within such a context. The idea of ‘bottom-up organisational methods’ has a utopian aspect to it and ‘permaculture gardening’ also comes out of a utopian tradition, so those two are underlying ideas within the project. But I like the word ‘utopia’ because it is open to interpretation and has a methodological element to it. It works like a metaphor, a figure of speech. For me, it’s a critical tool from which to frame certain problems or to question things.

Utopian thinking has often been criticized in the past, mostly because of its dangerous liaison with ideology. ‘Utopia’ alludes to this ideal society with perfectly happy people forcing others to share their happiness.

NN: Some see utopia as a dream space, a fantasy future society. That’s one part of it. Others see it as a critical tool with which to critique society and the conditions we live in, which is how I use it. Using the idea of utopia as a way of getting to another place, which doesn’t need to be a perfect place; it’s a way of moving out of the place we’re in to somewhere else. It’s a process rather than a goal.

PETER DE ROODEN (Stroom): That’s one of the reasons that our Stroom team was enthusiastic about Nils’s proposal, because it questions existing conditions, which was also the starting point of the Foodprint programme. A disconnection has been arising between city dwellers and their food sources, and between city dwellers and the hinterland where their food is being produced. This condition seems to be of relevance to all kinds of problems that one can see in the city. I don’t necessarily think Stroom or the arts are in a position to formulate the right answers to resolve this disconnection. Rather, I see Foodprint as a research programme to formulate various answers and to create experiments that test these approaches.

Edible Park is a collaborative project between you, as the artist, and Stroom, as the initiator and commissioner, and several local institutions like the Municipal Park Department and Permacultuurcentrum Den Haag, the voluntary permaculture organisation. How would each of you describe your own role in the process?

PDR: There are several roles, and in every stage of the project that role also changes. The first year, it was mainly getting the funding together, looking for spaces, organizing a building permit, creating a technical staff and so on. Now that the pavilion is there and the garden has been set up we are entering a new phase of the project. Actually, now is when the testing really starts. So the weight of the project is now shifting towards the group of volunteers that runs the place. We try to support them and coach them in setting out the next steps, both in terms of fundraising and creating relationships, but also to safeguard the aims that Nils Norman laid out for the project, its artistic character. In the coming months we will have to see how it could spread in the city and whether we as well as the volunteers can establish new collaborations.

Who would you then say is the ‘author’ of the project?

NN: That is what I like about this project, it shifts all the time. ‘Authorship’ is always an interesting problem, particularly within the art world. You are always forced into the role of the author because ideologically that is what is demanded of you. In art school you are taught to be an ‘individual’, an autonomous artist. This project blurs and questions that traditional definition of the artist. Sometimes I’m the author and sometimes I’m not. Sometimes I’m just a consultant. I’m sure that for most visitors to Edible Park the ‘author’ is Menno Swaak and Permacultuurcentrum Den Haag.

PDR: To me it feels like it’s a symbiotic balance of the different forces that are involved. There is a constant shifting of the balance; sometimes the focus is more on the domain of the permaculture, then we have to push it a little more toward the domain of the arts, and sometimes it should move a bit to the centre.

ORDER THE BOOK:

Nils Norman, Eetbaar Park | Edible Park

ISBN: 978-90-78088-61-5

Valiz, Amsterdam | Stroom Den Haag, 2012

€ 19,50

160 p, ills colour & bw, 17 x 24 cm, pb, Dutch/English

Authors: Nils Norman, Nina Folkersma, Agnieszka Gratza, Janna & Hilde Meeus met Menno Swaak, Fransje de Waard en anderen

Editors: Taco de Neef/Deneuve Cultural Projects, Nils Norman, Peter de Rooden, Astrid Vorstermans

The publication is part of the manifestation Foodprint. Voedsel voor de stad