Meschac Gaba’s Museum on the Moon

by Nina Folkersma

published in NKA, Journal of Contemporary African Art, no.9, 1998

“Money, money, money / Must be funny / In a rich man’s world“. I’d be willing to bet that everyone reading these words simultaneously hears the tune of the world-famous ABBA hit. It doesn’t matter whether you come from Sweden or from Burkina Faso, Japan or Venezuela; most likely you can immediately sing the refrain of this cheerful classic. It’s the sort of universal music that is equally easy on the ear – and equally meaningless – to everyone in the world. That is not true of another universal concept – money. Money is not at all meaningless or neutral. Everyone wants it, but for someone in Burkina Faso it means something different (and presumably has a different urgency) than for someone in Sweden.

Meschac Gaba, an artist from Benin living and working in Amsterdam for the past two years, is fascinated by money. A fascination closely related to the economic crisis in his native land and neighbouring countries in Africa. It all began when Gaba, wandering one day through the streets of Porto Novo, discovered a trash can full of shredded bank notes behind a bank building. You can just imagine his amazement! Confronted daily with the harrowing effects of a lack of money, he suddenly saw how this selfsame valuable stuff is simply cut up and thrown away. Meschac Gaba decided then and there to incorporate shredded bank notes – those ‘vouchers’ of the absurdity of our world economy – in his artworks. In his first works, the emphasis appears in particular to be on the formal, pictorial quality of the bank notes. The works he made on canvas all contain stamp-like imprints of organic forms which, because of the subdued ochre colours of Benin’s paper currency, are most reminiscent of the leaves of trees in varying autumnal tints. These are very different from the canvases Gaba covered with Dutch money. The shreds the Bank of the Netherlands makes of its old notes look like gaily coloured confetti.

Since his arrival at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam (the State Academy of Fine Art) in 1996, a more content-oriented shift has occurred in Gaba’s work. His ‘money pieces’, now primarily objects and installations, increasingly emphasize the economic relationship between the West and the African continent. Take a look at The Game of Democracy (1997) for instance: a chess set with chess pieces made from American dollars and French francs and a wooden board with bank notes from Benin used for the spaces. With this work, Gaba playfully and effectively exposes the underlying mechanisms of today’s world economy. Just like a game of chess, the market economy is dominated by the principles of competitiveness and the right of the strongest. Countries that are unsuccessful in adjusting their economies to changes taking place on the chessboard of the international marketplace are neglected – and ultimately shut out. The most recent statistics of the UNCTAD (the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) are patently obvious in this respect: 85% of worldwide direct foreign investment goes to the most developed countries. In other words, the rich invest in the rich; this forces the poorest countries to attune their economies to the production of goods for export, making them even more dependent upon the wealthy countries. The global ‘game of democracy’ is only a game on paper; on old and shredded paper, Gaba seems to be saying. As long as actual power – the power of money – is in the hands of the western world, contradiction and inequality will continue to exist.

Indeed, Gaba poses socially critical questions, but he averts heavy-handedness by the way he gives them form. He will always try to come up with a playful approach in order to preserve not only his own sense of humour, but also that of the spectator. Gaba likewise relates his questions to the art world, to the ‘business of art’. In point of fact, the economic relationship between the West and Africa has an undeniable impact on the way art institutions present other cultures. This became painfully clear to Gaba when he was confronted with the ambivalence so often surrounding African art in Holland. On one hand, interest in non-western art is growing, almost too prolifically it might seem, and on the other hand, western museums never fail to hoist national flags over their presentations of such art. In fact, the art of ‘elsewhere’ is still being treated as an anthropological phenomenon. Gaba artfully played up to this during the Rijksakademie’s Open Studios. In ’typical African’ street vendor fashion he spread a mat on the ground with his works displayed on it as if they were folkloric wares. But Gaba went a step further: he actually angled for money. With a T-shirt and a pamphlet, he prevailed upon every visitor to make a financial contribution towards setting up a Museum for Contemporary African Art.

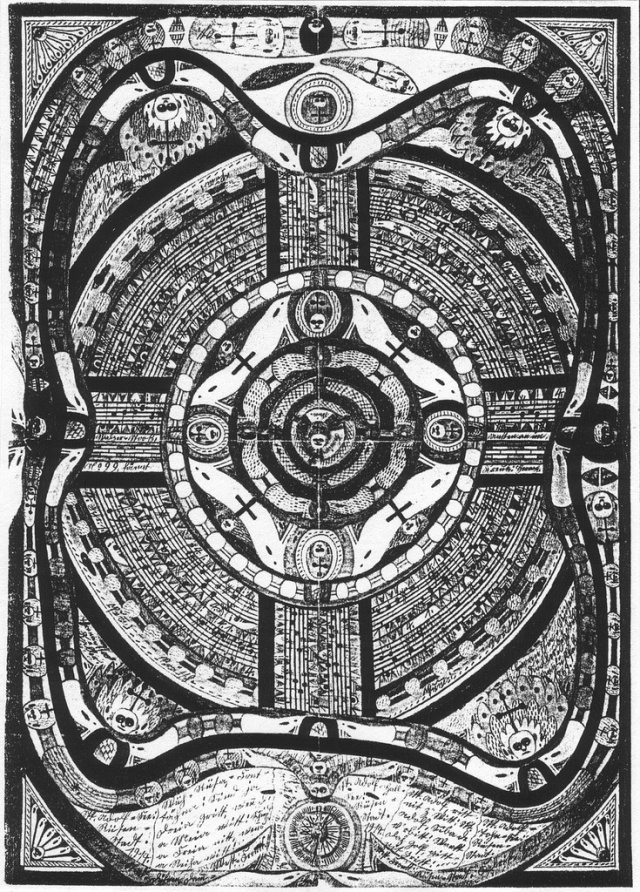

This museum, for now always temporarily housed in existing art institutions, is currently Gaba’s most important project. With this museum he wants to show that contemporary African art has long since passed the stage in which it could be reduced to a few so-called unique or original national characteristics. He opposes the often-heard notion that the work of a non-western artist is no longer ‘authentic’ if he uses the vocabulary of western modernism. This stubborn neo-colonial bias presupposes that modernism is a purely western attainment, conveniently forgetting that the West itself is also a product of exchange and mixture with other cultures. Gaba again reminded us of this during the presentation of his museum at the Gate Foundation in Amsterdam. In one of the rooms was a tree decorated with bank notes from various African countries. As an ironic counterpart to European bank notes, which frequently depict famous artists, Gaba had covered his notes with the faces of European artists who were inspired by African culture. Picasso hung there, for instance, portrayed as a president of Ghana, and dangling from another branch was Brancusi, in the guise of a militant general with his long white beard.

Meschac Gaba is a master at putting people on the wrong track. His work is full of little jokes and critical snakes-in-the-grass. When you ask him whether his future museum is a fictitious or serious proposal, his steadfast answer is, “that depends on you”. And if you should ask him where he would most like to locate his museum, in Africa or, contrarily, in the West, he answers just as cool as you please, “on the moon”. Not only because this offers a fantastic solution to the current deadlock in the ‘multiculturalism’ debate, but particularly because he’s looking forward to hearing the captain of the space shuttle say, “all aboard” and “fasten your seat belts please”.

(translation: Jane Bemont)